BLOG: There has been a shift in many post-Soviet countries’ efforts to improve the protection of children’s rights in child protection, resulting in fewer children in residential care. However, there are still challenges for ensuring the sustainable implementation of children’s rights.

Blog post by Postdoc Victoria Shmidt, UNIVERSITY OF GRAZ

Child protection in the fifteen post-Soviet countries challenges complex, contemporary approaches to exploring the development of ideas and procedures aimed at ensuring better implementation of children’s rights. What is the role of the legacy of the Soviet regime in the violation of children’s rights and the obstacles toward sustainability of child protection? How can we explain the differences in post-communist trajectories of child protection? The case of the post-Soviet space is instructive for revealing possible answers concerning the pressure of taken-for-granted suggestions on expertise in children’s rights. Exploring post-communist trajectories of child protection recognizes the impact of critical contextualization on equipping actors with a complex understanding of sustainable implementation of children’s rights that could not be reduced to opposing “bad” institutional care to “good” families.

A reduction in the use of residential care

The predominance of residential care during the late Soviet period, resulting in an enormous number of children placed into institutions of different types, continues to be the central and often only feature of Soviet child protection that occupies the attention of experts and those who aim to emancipate child protection from the Soviet legacy. Indeed, even in the last decade of the socialist regime, the mission of family placement started to be seen as one of the priorities for Soviet child protection policy.[1] After the crush of communism in 1989, deinstitutionalization started to be the main thrust for multiple initiatives, from the side of the government and international organizations.

Indeed, even in the last decade of the socialist regime, the mission of family placement started to be seen as one of the priorities for Soviet child protection policy.

VIctoria Shmidt

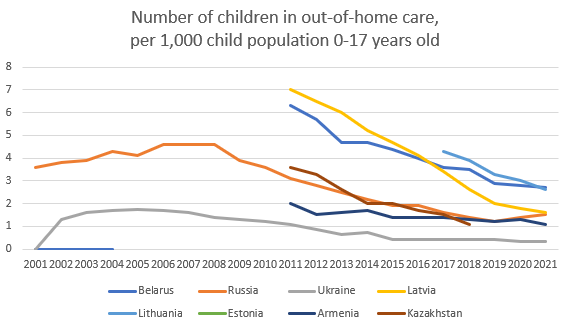

Between 2000 and 2009, the Unites States Agency for International Development initiated projects to transform large-scale institutions into family care centers in six of the fifteen post-Soviet countries.[2] Many international NGOs have partnered with local initiatives to improve the situation of children at risk of institutionalization. The flood of international support occurred during a period of significant political and socio-economic turbulence in the post-Soviet space, when economic crises and multiple military conflicts became the direct cause of the return to earlier orientations towards child protection: from threats to maltreatment, deprivation, and exploitation. Since the 2010s, national governments have assumed the main organizational role in the transformation, although the support of international organizations such as UNICEF and the EU Commission remains significant, especially in the regions of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Despite several waves of returning to residential care, by the 2020s, many post-Soviet countries had achieved impressive results in decreasing the number of children in residential care institutions (Figure 1).

Despite several waves of returning to residential care, by the 2020s, many post-Soviet countries had achieved impressive results in decreasing the number of children in residential care institution

Victoria Shmidt

At the same time, for children with disabilities or minors in conflict with law, placement into institutions still operates as a predominant option.[3] But can this shift be interpreted as ensuring the sustainable implementation of children’s rights?

Democratic challenges in child protection decision-making

Children’s rights, another protective orientation, stands in contrast to the historically more familiar ideology of protection against exploitation, deprivation, or maltreatment in post-Soviet countries. Drawing heavily on the rhetoric of a better future, Soviet ideology shaped the practice of child protection as part of building a better world without the legacy of “dark times”. Children were seen as future citizens rather than partners in the decision-making process. In children’s rights protective orientation, we see equal participation of children and parents in decision-making ensured by legal acts, as well as a variety of short- and long-term forms of placement as a precondition for the individualization of strategies aimed at protecting children.[4] Children’s rights rely on the democratic legitimation of decision-making, especially when the plausibility of conflicts of interest between the child, the child’s family, and protective services increases, along with the probability to limit parental rights.[5] And although Soviet rhetoric actively used the theme of children’s rights, the institutional design of decision-making in crisis situations hardly met the requirements of transparency and contestability, which are key for a democratic proceeding in conflicts regarding the best interests of the child.

By the end of the Soviet period, decisions regarding the limitation of parental rights and further placement of the child were being made by three main boards or commissions, consisting of the representatives of local authorities, educators, and medical practitioners: the Guardianship Commission was responsible for placement of children whose parents’ behavior was seen as irresponsible, the Commission on Juvenile Rights examined the cases of minors in conflict with the law, and the Medico-Psychological-Pedagogical Commission regulated the placement of children with disabilities. Among multiple damages for child protection this order of decision-making doomed many children to move from one institution to another without any chance for family placement.[6]

Although Soviet rhetoric actively used the theme of children’s rights, the institutional design of decision-making in crisis situations hardly met the requirements of transparency and contestability, which are key for a democratic proceeding in conflicts regarding the best interests of the child.

VIctoria Shmidt

The decisions made in the commissions’ administrative order were virtually irreversible, and there were no external forces able to offer alternative opinions. The problem of missing transparency and contestability in decision-making, which would minimize the risks of arbitrariness, is not exclusively a post-Soviet issue. . The power of child protection authorities and pressure of professional expertise remains a source of injustice around the globe for many reasons, including multiple manifestations of a utilitarian approach to children and childhood, and prejudice against groups like ethnic minorities, migrants, LGBT, etc. Furthermore, while the shortcomings in decision-making are under systematic examination and monitoring, we can nevertheless ask which of the post-Soviet countries consistently reform their approaches and make them more democratic.

The power of child protection authorities and pressure of professional expertise remains a source of injustice around the globe for many reasons, including multiple manifestations of a utilitarian approach to children and childhood, and prejudice against groups like ethnic minorities, migrants, LGBT, etc.

Victoria Shmidt

Latvia – an exception in the post-Soviet space?

Latvia is one of rare cases in the post-Soviet space that has implemented a consistent shift from the Soviet administrative order to a legal order of decision making. In 2007, “orphan courts” were introduced, modeled on those in some U.S. states, and the process of transformation in the principles underlying their activities is ongoing.[7] The mission of orphan courts is to represent children who neither live with their biological parents nor have been adopted. While orphan courts operate at municipal level, the call for making their decisions more transparent and contestable has led to two consistent reforms; in 2017 and 2022, the activity of the courts started to be supervised by the State Inspectorate for the Protection of Children’s Rights. One of the main practical tasks of these courts is to stop the practice of child removal in cases of poverty; rather, the courts are directed to pay more attention to cases of abuse and neglect. Latvia is the only country in the post-Soviet space that, among the regular data on child protection, provides information not only on the suspension and deprivation of parental rights, but also on the restoration of parental rights, which varies from 15 to 20 percent of the total number of decisions.[8]

Latvia is one of rare cases in the post-Soviet space that has implemented a consistent shift from the Soviet administrative order to a legal order of decision making.

Victoria Shmidt

The issue of decision-making in child protection is one that reveals the relationship between the post-authoritarian democratization of post-Soviet countries and policies regarding their future citizens. Questions about what is happening to child protection in states that move along authoritarian paths, such as Russia and Belarus, or how the vicissitudes in the field of children’s rights and democratic legitimacy are related in different geopolitical clusters, such as the Baltic States, Central Asia, or the Caucasus countries, continue to challenge experts and practitioners.

[1] Schmidt, V., & Shchurko, T. (2014). Children’s rights in post-Soviet countries: The case of Russia and Belarus. International Social Work, 57(5), 447–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872814537852

[2] USAID (2009) The Job that remains: An overview of USAID Child Welfare Reform efforts in Europe and Eurasia. Final Report.

[3] It should be taken into account that in countries with high labor migration, such as Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Russia, Latvia and Lithuania, children of migrant parents can be placed in institutions without being given orphan status and remain in institutions for several years. These children are not included in the official statistics. According to experts, the share of such “invisible” children in institutions ranges from 25 to 30 percent of the total number of children placed in institutions.

[4] Berrick, J., Gilbert, N. & Skivenes, M.(2023) “Child Protection Systems Across the World” in Berrick, J., Gilbert, N. & Skivenes, M. (eds.) International Handbook of Child Protection Systems Oxford University Press DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197503546.013.1

[5] Loen, M., & Skivenes, M. (2023). Legitimate child protection interventions and the dimension of confidence: A comparative analysis of populations views in six European countries. Journal of Social Policy, 1-20. doi:10.1017/S004727942300003X

[6] Schmidt, V. (2017) “Institutional Violence against Children: How to Cope with the Inevitable and the Unconquerable.” Background paper. Ending Violence in Childhood Global Report 2017. Know Violence in Childhood. New Delhi, India http://www.knowviolenceinchildhood.org/images/pdf/Schmidt-V_2017_Institutional_Violence_against_Children-How_to_Cope_with_the_Inevitable_and_the_Unconquerable.pdf

[7] Merle, L.and Strömpl, J (2023) ‘Child Protection Systems in Estonia and Latvia’, in in Berrick, J., Gilbert, N. & Skivenes, M. (eds.) International Handbook of Child Protection Systems Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197503546.013.15, accessed 19 June 2023.

[8] Siliņa, M. (2020) Children’s rights system in the Republic of Latvia in compliance with international law regarding out-of-family care system, Master Thesis, Riga Graduate School of Law