NEW ARTICLE: Postdoctoral Fellow Hege Beate Stein Helland has published her article on child rights in the prestigious journal International Journal of Children’s Rights.

The 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognizes both children’s participation as well as children’s best interest as essential rights, obligating the ratifying parties to implement and uphold these principles. However, successful implementation is often conditional on the institutional abilities and approaches.

In the article “Reconciling Children’s Best Interests and Right to be Heard” Dr. Helland examines the relationship between the child best interest principle and their right to be heard, by analyzing institutional approaches and empirical abilities of different national systems.

– After reviewing the literature, I propose a framework for understanding participation through a lens of a global typology of child protection systems, Helland states, adding that the data was gathered through conceptual and empirical reviews.

Participation of children crucial for their well-being

In addition to the essential legal obligation to safeguard children’s rights, the research also underscores the significance of children’s participation because it offers crucial insights into their needs, enabling decision-makers to craft more precise interventions and enhance their effectiveness. Moreover, integrating children into this process acknowledges their autonomy and individual rights.

– Listening to the voice of the child and subsequently getting insight into what the child wants assists decision makers to reflect upon what the individual child’s lifeworld looks like and to see the situation from the child’s perspective, Helland points out.

Furthermore, the article examines what role children’s voices can have, and there we can distinguish between “consultative”, “authoritative”, and “active” roles, with the latter being crucial for an integral approach.

– Theorists have different opinions on which of these roles is appropriate for children to engage in, but there seems to be rather broad agreement that the role of “active” participant is both desirable and feasible, Helland says. However, she adds, this demands that participation is more than merely hearing the child.

Different standards in participation of children

The analysis of different national systems shows that there are very different standards when it comes to the participation of children in decision-making. For instance, the minimum age when children have the right to be heard in decision-making proceedings, varies from some countries not having any minimum age requirements, and on the other hand Germany, with a minimum age of 14 years.

The article also analyses the commitment to include children in decision-making by providing an insight into legal frameworks and research of five countries: Ghana, Russia, Estonia, the Netherlands and Norway.

– It is evident from the overview that the institutional approach in all countries affirms children’s right to participation through its legislative commitments, and for all countries except Ghana, there are also policies that promote participation, says Hege.

Best interest model for participation

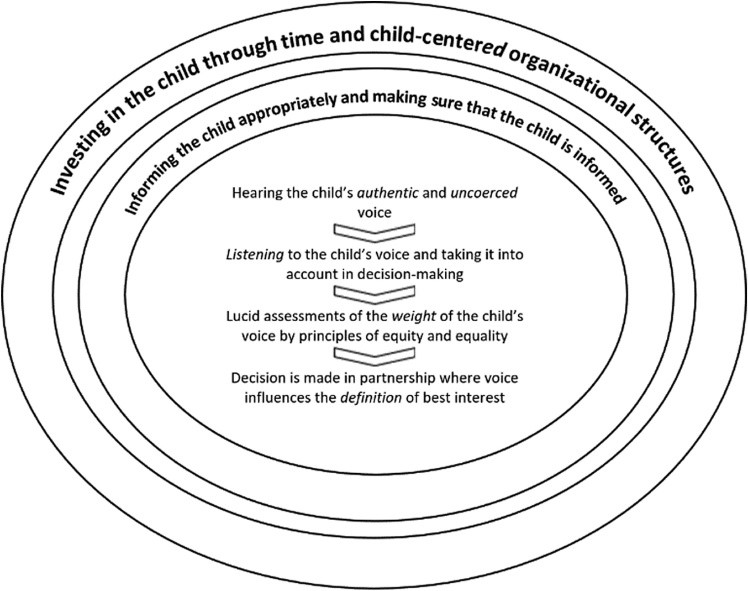

After analyzing both theoretical background and empirical examples, the author introduces a developed model aimed at reconciling between prioritizing children’s best interests and upholding their right to be heard.

– The model seeks global applicability, with the global child protection typology serving as a tool to guide implementation of children’s participation, granting cognisance to the challenges associated with different contexts, explains Helland.

The article is a part of the Legitimacy Challenges project, as well as the Discretion and the Child’s Best Interests in Child Protection project (ERC). It is open access and can be found here.