BLOG: Differences in Europe on what are important values and norms for children and families that are in child protection situation, may influence how legal standards as “undue hardship” and “child´s best interest” are understood. Findings from a population study from four countries display some clear contrasting findings on how people regard the importance of contact between a child living in a foster home and birth parents.

Blogpost by Marit Skivenes, Professor in Political Science, University of Bergen

Children in foster care have a right to have contact with their birth parents and birth family. This is clearly stated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), European Convention of Human Rights, and in national legislation in most countries we are familiar with. The right to family life is a human right that cannot be easily set aside, as the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHT) has repeatedly underscored in recent child protection judgments. However, a child’s best interest is a legitimate reason to restrict family life if it is shown necessary or proportionate. Contact is important and valuable for many children and parents in child protection, and it can be emotionally and practically burdensome but also unsafe for children, as is for example shown in the recent judgement in Hernehult #2 vs Norway, 2023, by the ECtHR.

A key consideration set by the ECtHR if there is doubt about the child´s interests and their wellbeing regarding contact with birth family, is to be found in the term “undue hardship”[1]. The interpretation and understanding of this criterion is not straightforward and is debated within legal jurisprudence and theory. For example, legal scholar, Professor Sandberg, ask if “undue hardship” is to be understood as if there should be as much contact as the child can endure, or if it is meant that there should be as much contact as possible without disregarding the best interests of the child (2020, p. 157). The Norwegian Supreme Court (2020)[2] is leaning towards the latter: “[T]he goal of reunification presupposes that as much contact as possible is given without disregarding the best interests of the child” (section 130-134). Further analysis of jurisprudence on this topic is welcome, but what is clear is that the principle of a child´s best interest is an important consideration. This principle is based on peoples and cultures normative values about family, children, childhood, and parenthood. Empirically, these values differ between countries and societies, and thus it is important to review the prevailing sentiments on these topics amongst people.

Ordinary people on contact

At the DIPA centre we have conducted a study of how ordinary people think about contact in child protection cases, and especially we examine considerations about potential burdens thata child may experience. For example, if a child expresses that they do not wish to have contact with their birth parents, how much weight should this be given? Or, if contact makes the child feel bad, or disrupts the child´s performance at school, or disrupts the child´s opportunity to be with friends. How should these situations and sentiments be handled? To ensure that people were thinking of a child with approximately the same capacities, we asked about a child of the age of 12 years old. See textbox at the foot of the post for survey questions.

We asked representative samples of the population in Norway, and we did the same for Finland, Poland and Romania. We expect Finland to be more child centric than Norwegians, but that citizens from Poland and Romania to be less child centric than their Nordic peers. With child centric here I mean that considerations to the child view and experience are more weight.

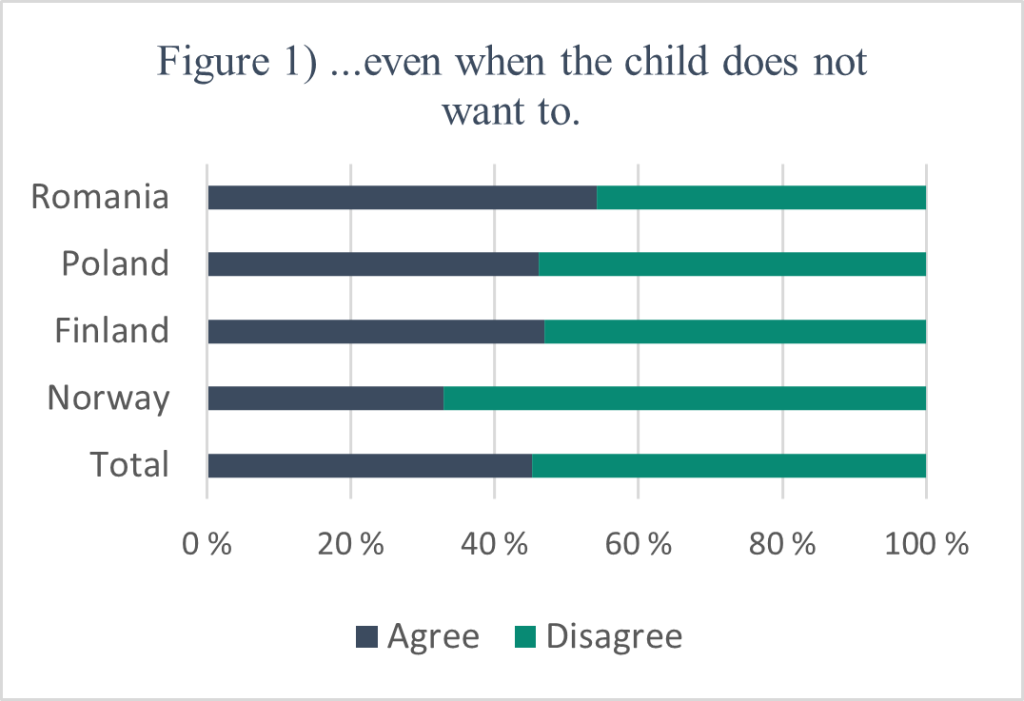

Child´s view

The results show that 45 percent of the full sample agrees that a child should have contact with birth parents, even when the child does not want to. Far less Norwegians agreed to this, 33 percent, in Poland it was 46 percent that agreed, in Finland 47 percent and in Romania it was 54 percent (see figure 1). These findings indicate that children´s rights to participate have a strong standing in the Norwegian society, clearly stronger than in the other three countries.

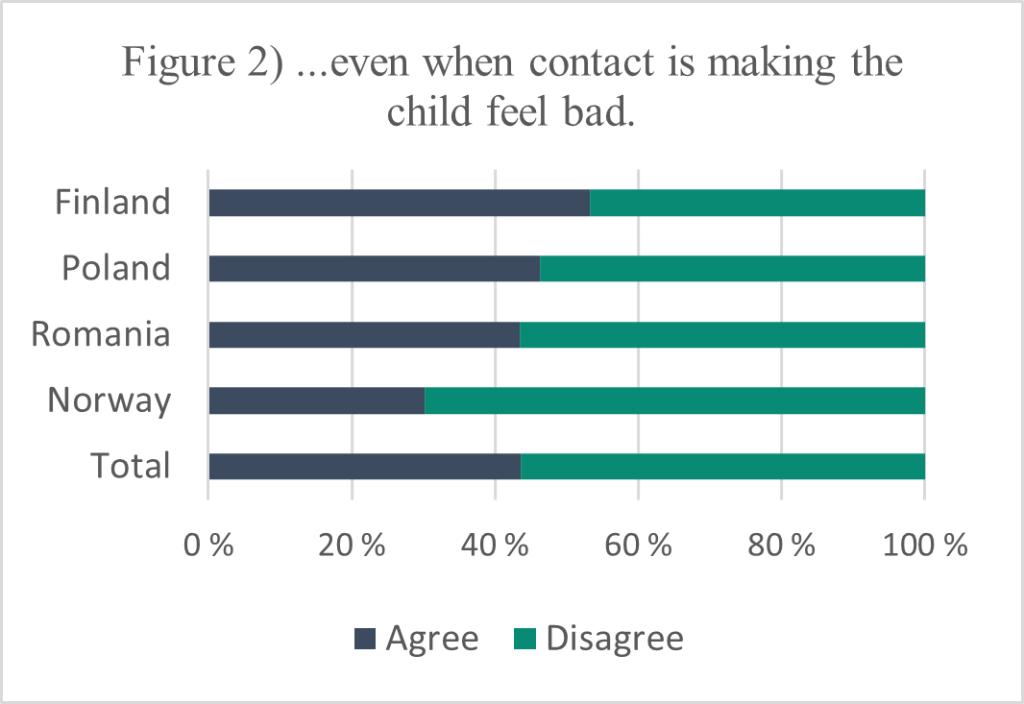

Child´s wellbeing

In terms of the situation that contact makes the child feel bad, a total of 44 percent agreed that contact should still take place. However, also here it is clear Norwegians differs significantly from the other three populations, with 30 percent agreeing compared to 43 percent in Romania, 46 percent in Poland, and 51 percent in Finland (see figure 2). These findings indicate that Norwegians are particularly focused on a child´s wellbeing and to protect children from harm.

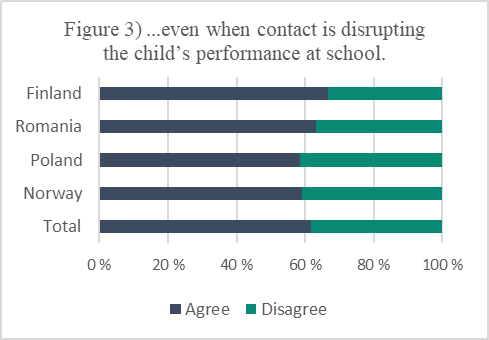

Child´s education

Education is important for a child’s future and opportunities to choose a profession according to interests and skills. A total of 62 percent of the total sample agreed that contact should happen even if contact disrupts a child´s performance at school. The differences between the populations were less for this dimension, and Norwegians and Polish respondents are similar with 59 percent and 58 percent agreeing that contact outweigh education, respectively. In Romania 63 percent were agreeing, and in Finland 67 percent were agreeing (see figure 3).

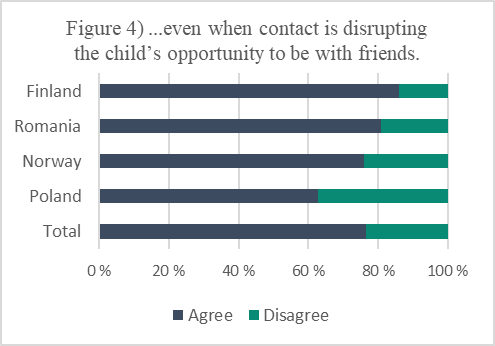

Child´s friendships

The fourth dimension we examined was a child’s opportunity to be with friends, as friends are an important part of many teenagers’ life and way to develop relations and friendships. For this dimension a total of 76 percent agreed contact should outweigh a disruption of being with friends. Only the Polish population stood out, with 63 percent agreeing, followed by Norwegians (76 percent), Romanians (81 percent) and Finns (86 percent).

Due hardship – a cultural matter?

The result from this study indicates that there are some values and norms for children and families that differs between societies, and thus are likely to influence the interpretation of legal standards as “undue hardship” and “child´s best interest”. Especially, Norwegians emphasize on a child´s view and a child´s well-being, are indicators that the cultural climate in Norway and the understanding of child rights in the society differs from the three other countries included in the study. Further analysis is required, and a peak into the upcoming analyses reveals that men, older people and those that accepts corporal punishment are more likely to agree that contact must take place against the child´s wishes, well-being, and educational considerations.

[1] See K.O. and V.M. vs. Norway 2019, section 68, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-198580%22]}; Sandberg (2020). Storkammeravgjørelsene om barnevern. Tidsskrift for familierett, arverett og barnevernrettslige spørsmål [Grand Chamber decisions on child protection. Journal for family law, inheritance law and child protection law issues], 18(2-2020), 148– 159.

[2] HR-2020-662-S. Authors translation.